Part 3: Hockenhull Platts

The Destruction of the Platts bridges?

Introduction

For centuries, responsibility for the upkeep of the Platts and its bridge was always in doubt, despite being the main London to Holyhead road. It needed a secure bridge crossing of the Gowy but constant neglect saw its deterioration to the point of failing in 1621. The loss of the bridge demanded the intervention of King Charles II and Justices of the Peace.

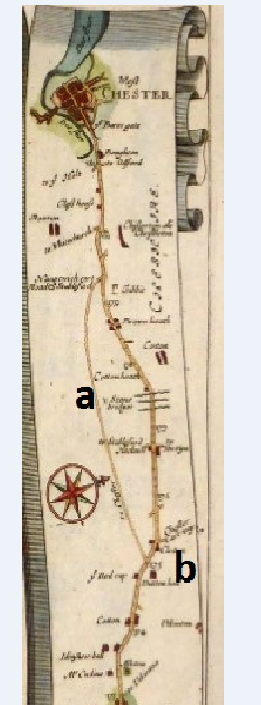

In 1674, the King instructed John Ogilby to map the principal roads of England and Wales. Published in 1675, the Britannia Road Atlas, showed 'three stone bridges' at Hockenhull. It would appear major action had been taken to ensure safe passage on the King's Highway through the Platts. Not only were the bridges constructed but a causeway linked them together. Building the bridges and a substantial causeway was a major engineering feat at considerable cost.

Oligby's strip map of Hockenhull

The construction of the bridges at this time, necessary as it was, could not have foreseen the decline of the Hockenhull route due to the changes in transport that were coming. Yet, there are design features in the bridges that showed these changes in transport were already underway. Features both serving the needs of packhorses and the likelihood of increased wheeled traffic.

The invention of turnpiking roads was an imminent and serious threat to long-established routes such as the Platts. A charge was required to use these turnpike roads. Such of tolls would have been a costly burden to the packhorse trade enough to seek alternative routes.

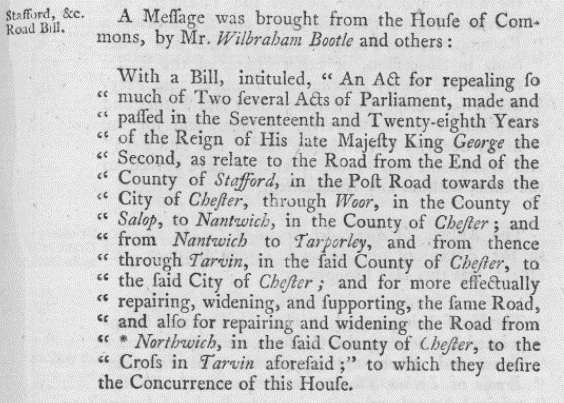

Acts of Parliament granted individuals the opportunity to invest in turnpike trusts. The aim being to maintain local roads and bridges by levying tolls and in so doing make investors profits.

A turnpike was basically a horizontal bar or gate across a road and opened on payment of a toll to pass through; generally, pedestrians were not charged. Some main roads had a number of toll-gates. Charges were displayed on a board against a toll-house by the road side.

The upkeep of roads and bridges transferred from the parishes to turnpike trusts. For centuries the parishes had carried out the task of local road maintenance. Turnpikes were both a blessing but as their number grew, became an equally burdensome.

Created by private investors in the late 17th century such trusts grew rapidly in the 18th century as more turnpikes were set up by act of Parliament. As part of the King's Highway the Platts route came under serious consideration to be turnpiked. The route was extremely busy and offered trust investors a very profitable venture.

Whether the Platts route was ever turnpiked is not clear. One source appears to offer some clarity.

By 1729, the London to Chester road had been turnpiked as far Lichfield and to Nantwich in 1744, renewed in 1761. An additional Act in 1769 sought to allow the collection tolls north of Nantwich.

'Under the acts of 1744 and 1761, 'the Trustees were restrained from erecting any Turnpike between Nantwich and the City of Chester, which is about Twenty miles.... The 1769 Act had re-routed the turnpike through Tarvin rather than via Stapleford'.

The 1744 Act excluded Hockenhull from being turnpiked.

One source gives the turnpike section as 'from Woore-Nantwich-Tarporley-Duddon-Chester, came into operation in 1744; this took the medieval route over the three Hockenhull pack horse bridges via Christleton to Chester'1

The 1769 turnpike route followed the cart way (shown on Ogliby's map) through Tarvin and Stamford Bridge. The trust was refused permission by the Grosvenor Estate, to send the road through the Platts.

Another attempt, in 1824, this time by Cheshire County Council, to divert the Nantwich to Chester road via the Platts was refused by the Marquess of Westminster.

Hockenhull Platts and its bridges and causeway survived.

The turnpike trusts revolutionised roads and travel times in the late 18th and early 19th century. For the majority of working people the tolls were a tax on their free movement and were greatly resented. There was opposition, none more so than from the packhorse and drovers trade using the Platts route, for the tolls would have been their undoing. At a 1 penny at least per horse, the cost to a packhorse train passing through a tollgate would cost 30 pence or 2s 6d. If the day wage for a labourer was 20p a day, the turnpike roads signalled the end of a major part of the packhorse trade. Unsurprisingly those which continued sought alternative routes.

By the time the turnpike toll gates were finally removed in Britain in the 1890's the competition from canals and railways was very much underway.

To-day, Hockenhull Platts remains a quiet, historic bridleway with its unique bridges. The bridges, the causeway, and Platts Lane remain much as they did in 1675. There are alterations to the bridges though nothing to suggest turnpiking. It did not happen.

Any feedback please to dbkeogh@hotmail.com

Quick Links

Get In Touch

TarvinOnline is powered by our active community.

Please send us your news and views.