Tarvin Birds: – The Grey Heron

Tarvin Birds:

[

]

The Grey Heron.Ardea Cinerea

The heron has been seen during only one of our monthly woodland bird surveys, and that was back in February 2017! However, the residents who live close to the woodland saw a heron perched on a tree overlooking the Tarvin Primay School field on several occasions last summer. So we appear to have a heron (or, perhaps, a number of herons) that are fairly regular visitors to our woodland (and, I suspect, more importantly, to the gardens that bound it). I will come back later to the question of why a bird that is seen so seldom during our surveys might have sightings reported to us so frequently!

Herons belong to the group of birds that include Storks, Egrets, Spoonbills and Bitterns. All of them have long legs with particularly long toes, which are very useful when wading on soft mud. Their wings are broad and rounded, often markedly bowed in flight, and they all have long sinuous necks and dagger-shaped bills. Grey herons are unmistakeable: they are tall, with long legs, a long beak and grey, black and white feathering. They are able to stand with their neck stretched out, looking for food, or hunched down with their neck bent over their chest. In my youth, the only one of these birds that I might have seen in nature was a heron – bitterns were native to Britain but not to areas where I might have been and egrets did not arrive in the UK as breeding birds until perhaps 50 years ago – another example of the wider effects of changes to our climate. There are of course spoonbills in the Zoo but, for simplicity, we will exclude them!

I can date my first sighting of a heron very precisely. It was on the afternoon of Sunday 14th May (Whit Sunday) in 1978. Having moved into Tarvin at Christmas 1976, we worked solidly throughout our first year to try to sort out the house (and, truthfully, we aren't quite there yet!). By Spring 1978, we really needed a holiday and so we booked a week cruising on the Trent and Mersey Canal, starting from Barnton. We set off in the early afternoon and, by teatime for our tiny children, I found myself alone, piloting the boat where the canal seems to pass through the Northwich flashes. Suddenly, a large, awkward-looking grey bird flew up ahead of us and settled again amidst the reeds at the edge of the flash. I now knew what it was that I was seeing and I went from never having seen a single heron to being able to count a dozen or more of them, quietly fishing for their tea, in only a minute or two! That first meeting with herons, at the age of 33, ranks as one of my more enduring memories.

The grey heron is often seen stood as still as a statue on its long thin legs, patiently waiting for its next meal to swim by in the shallow waters of the ponds and lakes that can supply its food. The water needs to be either shallow enough, or have a shelving margin in it, to enable them to wade. Their food is mainly fish, but they will also take small birds (such as ducklings), small mammals (like mice and voles) and amphibians (for instance frogs, toads and newts). They stand motionless in the shallows, or on a rock or sandbank beside the water, waiting for prey to come within striking distance. Alternatively, they move slowly and stealthily through the water with their body less upright than when at rest and with the neck curved into an "S". The heron has a surprising ability to straighten its neck very quickly and strike in order to spear its prey with its bill. Small fish are swallowed head first, while larger prey and eels are carried to the shore where they are subdued by being beaten on the ground or stabbed by the bill. They are then swallowed, or will have chunks of flesh torn off them. The main periods of hunting are around dawn and dusk, but they are also active at other times of day. At night they roost in trees or on cliffs, where they tend to be highly gregarious.

Herons nest in colonies called 'Heronries', often in the top of trees, and I suspect that our closest heronry might be on the River Dee. Here, they make their large, ungainly nests out of twigs, with the same nest being used year after year, until it is blown down. It starts as a small platform of sticks but expands into a bulky nest as more material is added in subsequent years. It may be lined with smaller twigs, strands of root or dead grasses, and in reed beds, it may be built from dead reeds. The male usually collects the material, while the female constructs the nest. Breeding take place between February and June. When a bird arrives at the nest, a greeting ceremony occurs in which each partner raises and lowers its wings and plumes. A clutch of eggs is typically 3 to 5 eggs, which are normally laid at two-day intervals and incubation usually starts after the first or second egg has been laid. Both birds take part in incubation and the period lasts about 25 days. Both parents bring food for the young. At first, the chicks seize at the adult's bill from the side and extract regurgitated food from it, but, later, the adult disgorges the food at the nest and the chicks will then squabble for possession. They fledge at 7-8 weeks old. Usually, a single brood is raised each year, but two broods have been known. The average life expectancy of a heron in the wild is about 5 years but the oldest recorded bird lived for an amazing 23 years! Regrettably, only about a third of juveniles survive into their second year, many falling victim to predation.

Herons will travel miles in search of food but, since they are so dependent upon expanses of shallow water – of which our woodland has none – why might we be getting so many reports of them being seen in our neighbourhood? I have a suspicion that, in this case, our woodland is not itself a destination for the birds. Rather, I think that it might be a convenient corridor between the places of real interest to the herons – the neighbouring gardens with ponds. Herons are known to visit garden ponds in search of a quick and easy snack. Even if the pond does not have fat, juicy koi carp for the bird to feast on, it is quite happy with a few goldfish, and there might still be populations of newts or frogs that can provide a quick repast. Could it be that the sightings of herons are as a result of Tarvin's kind householders providing buffets of fish or amphibians for these intriguing birds in their gardens?

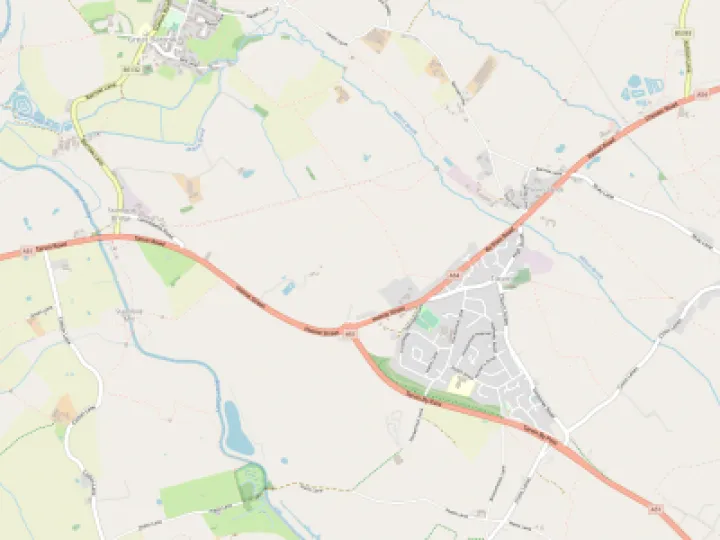

Other sightings of these birds over the past two years or so have been in the fields behind and beside St Andrew's Church. The River Gowy flows through this area and there have been some reports of otters in the Gowy. Where there are otters, there must be food. We would be interested to hear of future sightings of herons in Tarvin but as well as when the sighting took place, would you also tell us EXACTLY WHERE you saw the bird(s) and what they were doing at the time? Let's see if we can solve this puzzle once and for all!

Ed: I've seen a Heron on trees overlooking the school field, and even a cormorant on a rooftop in Tarvin. Where there are herons and cormorants, there must be fish not too far away. Perhaps the Gowy is better stocked than we thought?!

Quick Links

Get In Touch

TarvinOnline is powered by our active community.

Please send us your news and views.