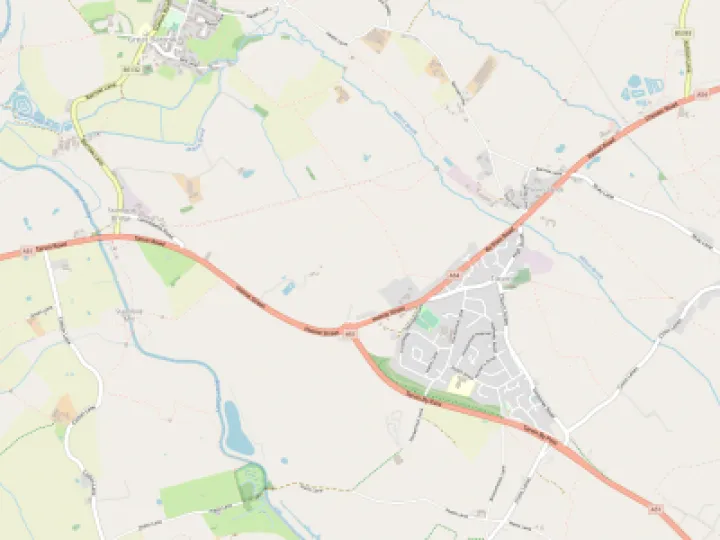

Rivers may seem to be permanent features of the landscape though this is a relative matter in historical terms. Flowing across different rock types conditions the course of a river. A river such as the Gowy does not pass through the school geography stages of youthful, mature and old age. Its course is dominated by a low gradient producing a meandering journey across a shallow, virtually non-existent valley.

Today's Gowy has seen a long history of climate change and human intervention. At various times its character showed a very different side. Land drainage and the reclamation of marshes required dealing with the annual flooding by the river. In so doing the river is flowing straighter, faster and reminiscent of its true nature. Human intervention has so complicated the river's character as to corrupt its journey to the Mersey.

"The River Gowy used to be a more powerful stream, running wider and deeper than today as the water table has dropped and engineers have reduced it to a smooth flowing ditch." (Elspeth Thomas, The Story of Kelsall, 1988)

'We remember, in the 1950s the river being fast flowing and the bottom very gravelly. Our children would canoe down towards Stamford Bridge." (Previous owners of Hockenhull Hall)

Information about the Gowy comes in the form of fragments relating more to the bridges than the river itself. The Black Prince's Register records a grant of 20s in 1353 for the repair of Hockenhull bridge. Such a sum points to a major repair but nothing about the river. Two centuries later, the plea by Hockenhull parish in 1614 to repair the bridge does not mention the Gowy. Only William Webb's c1621 observation of the Gowy, without a bridge, offers a reasonably confident reference.

"At the one side of which demesne lies Hockenhull plat, a place well known, being the passage over our said water, in our great London road-way to Chester, wanting nothing but a bridge for carts to pass that way when the river riseth, which were very necessary and charitable work to be done." From Itinery of Eddisbury Hundred by William Webb reprinted in G.Ormerod, The History of the County Palatine and City of Chester, 1882 Vol II p.8.

Ogilby's map of 1675 shows a section from Tarporley to Chester via Hockenhull describing: "Hocknel another small village, you pass 3 Stone bridges so many rivulets, and Cotton Heath."

Clearly, rivulets suggest no main river was visible so why build three stone bridges? An earlier article, 'Crossing the Hockenhull marshes ' queried Ogilby's recording of the bridges suggesting instead a causeway with culverts on the lines of the one below, in flood conditions.

The maps of Burdett (1777), Greenwood (1819) and Bryant (1831) do not indicate more than one bridge and one river. This is hardly surprising considering these are mapping counties rather than the small narrow roadside features of Ogilby's strip map. Nevertheless, his brief description at Hockenhull is, compared to all other cartographers, the first to give an idea of the situation at Hockenhull. Just when the Gowy emerged from the marshes as the dominant watercourse is unclear.

Hockenhull bridge suffered its major failures in the 14th and 17th centuries when Britain's climate was changing to prolonged cooler and wetter seasons. The 1280s to the late 1340's suffered cold, wet seasons and floods, alternating with droughts but it was not until the early 1600s that the Little Ice Age really set in.

The failure of Hockenhull bridge on both occasions was the culmination of years of neglect. In its rebuilding, stone masons knew of the past strength of the river but even so, it wasn't enough. To-day, the scarred bridge remains but the Gowy has moved. Since the 14th century it has moved four times including diverted in 1945.. However, its course, and more interestingly, its marshes, have been determined millions of years ago.

Quick Links

Get In Touch

TarvinOnline is powered by our active community.

Please send us your news and views.